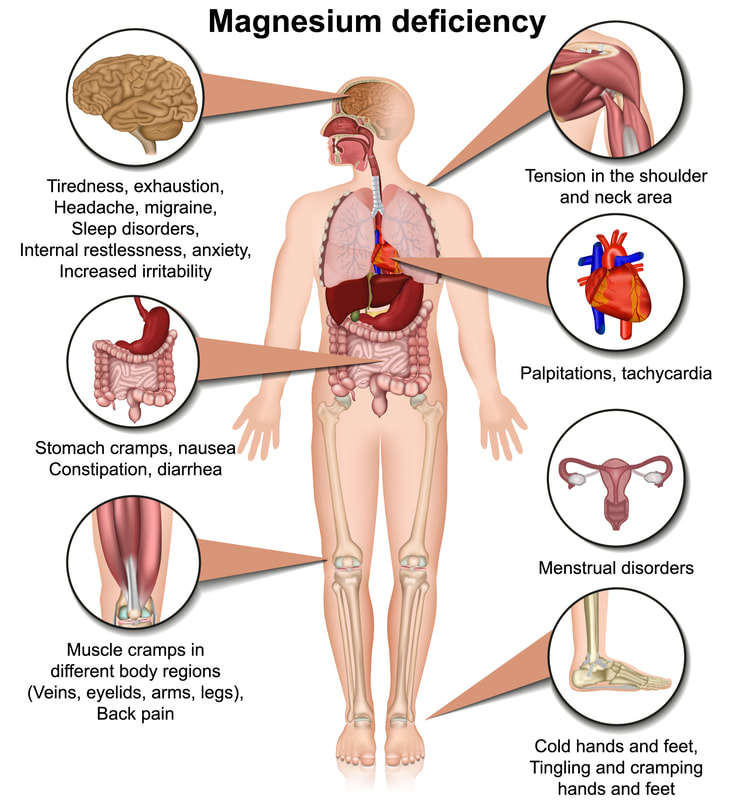

Magnesium is an important mineral that we get from the diet and is found in a diverse array of whole foods. It is a hot nutrient topic right now and for good reason. Although commonly seen in hospitalized patients, the general "healthy" population is now estimated to have a high level of deficiency that is going unchecked. This is concerning as magnesium supports many pathways and functions in the body including but not limited to: bone support, hormone functioning, blood clotting, and DNA replication (1). A deficiency could contribute to, or worsen, chronic conditions, as well as promote new health concerns. As health care practitioners it is difficult to bring awareness to this need as the symptoms of deficiency are vague: fatigue, lethargy and muscle weakness; and can easily be mistaken for other issues (1). There are also challenges in the serum reference ranges for testing and it is difficult to detect reductions of the magnesium in tissues, so baseline for supplementation can be challenging (1). The standard RDA (recommended dietary allowance) for adults is variable and depends on age and biological indicators. In general the recommendations are around 400 mg/ day which is the typical dose available in over the counter supplements (1). The good news is that magnesium is found in many foods and eating a whole foods based diet with a variety of items is a good way to meet your needs without the need for supplementation. It is important to note that food processing does diminish the magnesium content of many food items so choosing organic whole foods (if possible) is the best way to ensure you meet your needs. If you feel supplementation is still the best choice for you, talk to your provider to make sure there are no health reasons that you should not supplement. If you do choose to supplement be sure to purchase a quality product to ensure the best absorption, with nutrients and supplements quality really does make a difference. Magnesium Food List from the NIH Data Base

References

1. Gropper, S., & Smith, J. (2017). Advanced nutrition and human metabolism (7th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing/Cengage Learning. 2. National Institutes of Health Office of Dietary Supplements. Magnesium Fact Sheet for Health Professionals Accessed 05/06/2021.

0 Comments

I receive a lot of questions about bariatric surgery and potential malabsorption concerns with it so I thought I would share some evidence around some common deficiencies and complications with those deficiencies.

Which nutrient deficiencies might cause neuropathy? The nutrient deficiencies that could contribute to, or be the cause of neuropathy are vitamin B1, B12, B6, vitamin E, and copper, which is associated with optic neuropathy (Becker et al., 2012). Vitamin B2 also causes “burning feet syndrome” which can be a sign of peripheral neuropathy (Martin, 2018). How would you differentiate which nutrients might be responsible for neuropathy? It is not always easy to isolate which nutrient deficiency is responsible for the reported neuropathy in the patient. There are several factors to consider when reviewing patients symptoms, but one major consideration is the time of the onset of symptoms, most neuropathies present years after bariatric procedure (Becker et al., 2012). Thorough review and assessment of patients diet, nutrient status, and medical history should be conducted when presented with neuropathy (Becker et al., 2012). Assessing the specifics of the neuropathy such as the time of onset and how it presents is a good starting pointing (Becker et al., 2012). Then testing for specific nutrient deficiencies and ruling out other potential causes is a good way to work on isolating which type of deficiency is present (Becker et al., 2012). Which micronutrient is most likely to show deficiency first? Thiamine deficiency usually presents within 8 – 12 weeks post-surgery but can be seen as early as 6 weeks (Becker et al., 2012). In my experience in working for a bariatric program for the last five years, in which three of those years I was the Program Coordinator, we most often saw thiamine deficiency. It was also challenging to get doctors to always identify this as the issue. One patient in particular had a history of alcohol abuse and he was often brushed off on the assumption that perhaps he had started drinking again. Thankfully he presented to the ER one day when one of the more progressive providers was working and he contacted me to discuss his symptoms and together we were able to identify thiamine deficiency. An easy blood test identified this. I have also worked with clients who did not have good medical coverage for additional lab work and their insurance providers did not cover some of the nutrient testing that I felt they should routinely have. What are the general supplement recommendations for most bariatric surgery patients? In the clinic that I worked we would routinely recommend a B complex, B12, Vitamin D, Calcium (although this is debated), vitamin C (for healing), Multivitamin, Iron (on occasion- not for everyone), and then others based on patient’s needs. From my own research I would also recommend K2, CoQ10, fish oil, and magnesium. I will say that we only performed Sleeve Gastrectomy and the surgeon I worked with INSISTED that this was not a malabsorptive procedure and therefore there was no need to supplement if patients were able to meet their nutrient needs via the diet. To support him and also do my duty as a dietitian I would confirm what he said but also reiterate the fact that they most likely will not be meeting their nutrient needs simply by the fact that their portions are so small and for many weeks they are utilizing liquid nutrients which may not be as absorbed so supplementing could help prevent deficiencies later on. Most patients agreed with this and were happy to supplement. The sleeve gastrectomy makes it easier to use any type of vitamin, but I did have a lot of clients start to look into vitamin patches per information they learned from their support groups and bariatric blogs. This is an area that I admittedly have not had the time to dive into, but I do think it is curious as we do absorb things well trans dermally. According to the text and the readings, the common supplement recommendations post bariatric surgery are vitamin A, thiamine, B12, Folate, Iron, Calcium, vitamin D, vitamin E, vitamin K and Copper (Becker et al., 2012; Litchford, 2013). B12 deficiency is common in patients aged 50 and older. Long-term deficiency can cause permanent neurological damage. B12 deficiency is missed in many patients because symptoms are vague, worsen progressively, and serum levels are a poor indicator of sufficiency. Outside dietary insufficiency, list at least two causes of B12 deficiency. Two common causes of B12 deficiency that are seen frequently by dietitians are: medication use that reduces absorption of B12, and post-bariatric surgery status (Litchford, 2013). The medications that typically affect absorption most likely to be seen in a nutrition consult are proton pump inhibitors and metformin (Litchford, 2013). Bariatric Surgery includes both the Roux-en-Y procedure and the Sleeve Gastrectomy (Litchford, 2013). Why does the risk of B12 deficiency increase with age? What is the mechanism? B12 deficiency is more common in the elderly population because there is an increased risk for a decrease in nutrient intake, and there are increased challenges to absorption of nutrients in the aging body (Litchford, 2013). Some of the signs and symptoms of B12 deficiency are more common and expected in the aging population so can be unidentified until later stages of the condition (Martin, 2018). Nutrient intake amongst the elderly is more common because of a number of factors including but not limited to; decreased appetite, chewing and swallowing difficulties, changes in tastes, access issues to healthy foods, and cognitive impairment (Litchford; 2013). B12 deficiency at its end stage is known as pernicious anemia and is the result of a prolonged reduction and loss of the synthesis of intrinsic factor which is essential for the uptake of B12 (Litchford, 2013; O’Leary & Samman, 2010). In the ageing population this can be diminished for a variety of reasons, one of which is the use of certain medications for conditions that correlate with ageing (Litchford, 2013). Which medications increase the risk of B12 deficiency? The medications that are commonly known to increase the risk of B12 deficiency are: omeprazole, lansoprazole, Tagamet, Pepcid, Zantac, cholestyramine, chloramphenicol, neomycin, colchicine, metformin, nitrous oxide anesthesia, and some epileptic medications (Litchford, 2013; Martin, 2018; O’Leary & Samman, 2010). Becker, D. A., Balcer, L. J., & Galetta, S. L. (2012). The neurological complications of nutritional deficiency following bariatric surgery. Journal of Obesity, 2012, 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/608534 Litchford, M.D. (2013). Nutrition focused physical assessment: Making clinical connections. Case Software. Martin, C. (2018). Detect nutrient deficiencies with NFPE. Today’s Dietitian, 20(3), 42. O’Leary, F., & Samman, S. (2010). Vitamin B12 in health and disease. Nutrients, 2(3), 299-316. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu2030299 (Links to an external site.) |

Details

Archives

June 2024

Categories |

|

Jessica Carter MS, RD, LD, CDE, RYT200 1900 Division ST W, Unit 4, Bemidji 218-556-9089 |

|

Copyright © Core Health & Nutrition, LLC.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed